Superintendent of Schools Joseph Kobza recently announced that, for the first time in history, all three of the town’s elementary schools — Monroe, Stepney and Fawn Hollow — were recognized as Connecticut Schools of Distinction in the same year.

The following story is the second in a three part series highlighting each school.

MONROE, CT — Monroe’s public schools have 81 children who moved to the U.S. from other countries. These students speak 13 different languages, from Spanish and Haitian Creole to Vietnamese, and more than one-third of them attend Stepney Elementary School.

The success of Stepney’s English as a Second Language program is among several reasons why it earned Connecticut School of Distinction status for 2021-22. Principal Ashley Furnari said Stepney has 31 English language learners (ELL) and will have two more after the winter break.

“We welcome these families,” she said. “The voice of our children is so important.”

The Connecticut State Department of Education recognizes participating schools whose students excel on the SBAC test as Schools of Distinction.

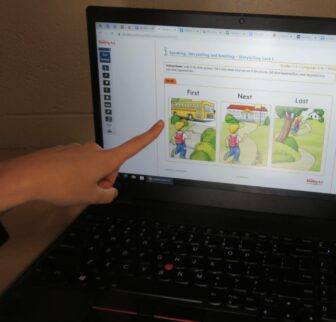

One recent Friday morning, Melanie Vieira, an English as a second language instructor for grades k-5, worked with two young girls in her office, Anna from Ukraine and Bea from China.

Vieira’s computer screen showed three drawings of a boy with a backpack. The first one, on the left, showed him walking on a sidewalk, while waving at a school bus he was heading toward.

In the middle picture, he walked toward a school building. Then in the third, to the right, the boy walked toward a house.

“I think he went home after school,” Vieira said. “What about you Anna?”

The girl agreed.

“After the bus, when you get home, what do you do?”

“I walk to my house and do my homework,” Anna said, taking it a step further.

This lesson was on sequencing. In another, Vieira said she worked with two sisters from Ecuador on the months of the year, corresponding with seasons and what the weather is like.

“I speak Portuguese fluently and can speak Spanish,” Vieira said.

When teachers do not know a student’s native language, Furnari said, “we’re using ear pod devices to bridge that gap. They don’t always work perfectly. It’s an accommodation. It’s part of their tool kit, as well as having supportive friends and teachers.”

But ear pods do not include every language, so other strategies are also used.

ELL in the classroom

“At the beginning of the school year I use a lot of hand gestures and picture books, modeling behavior and pointing out what other kids are doing,” said Meegan Garrity, a kindergarten teacher.

Garrity said students point to pictures for nonverbal communication. She also showed a sheet with photos of Kataya, who speaks Haitian Creole, illustrating expected behaviors, including “work at the table”, “sit on blue foam”, “raise a hand”, “use a quiet voice” and “walk in the hall”.

When Kataya displays these behaviors, she is rewarded with stickers on the back.

Garrity has Kataya and another student from Guatemala in her class.

“Both students are using small English phrases in appropriate ways to communicate with their peers,” Garrity said. “They love coming to school and they’re happy and grateful every day. One said ‘Feliz Navidad’ yesterday. That was cute. Kataya says hello. She wants to greet everybody.”

In kindergarten it’s an easier start for ELL students, because children are already learning the letters and sounds of each, and there’s a lot of movement and imagery in the classroom, according to Vieira. “You’re learning these basic things,” she said.

By contrast, Vieira said research shows it is harder to learn a language post puberty.

There are also other challenges English as a second language teachers face. For instance, Vieira is working with a fourth grade boy from Vietnam.

“I won’t be able to help him with his native language,” she said. “It’s not alphabetic, so we’ll have to teach him the alphabet right away.”

‘Support they deserve’

“It’s amazing to watch Monroe’s demographics changing,” Vieira said. “ELL is the fastest growing population in our schools in America and it’s important that we support that change appropriately.”

“It’s amazing to watch Monroe’s demographics changing,” Vieira said. “ELL is the fastest growing population in our schools in America and it’s important that we support that change appropriately.”

ELL students primarily learn in their classrooms and are pulled out for services. But staffing is thin, so oftentimes Vieira only sees students twice a week.

“My time is very limited with 32 students and I’m working part-time,” she said. “I make time specifically for teachers with children with high needs and limited-to-no English.”

Cindy Madeira, the other k-5 English as a second language instructor in the district, works full-time for Monroe’s other two elementary schools.

“I have 32 students. She’s somewhere in the 40s,” Vieira said. “Luckily they did approve me to be full-time next year, which is much needed,” she added of the latest education budget proposal.

On Stepney’s English as a Second Language program helping it attain Connecticut School of Distinction status, Vieira said of her students, “the other kids are welcoming to them at Stepney Elementary School and the teachers have done a great job of modifying their instruction.”

“I’m so proud of that. It really shows the classroom teachers are doing what they’re supposed to be doing,” she said, “but I think next year will be an even bigger step, because they’ll be able to get more appropriate support that they need, require and deserve.”