MONROE, CT — Monroe was long known for its epic budget battles, when voters defeated town budget proposals at several referendums each year, before one was adopted for the next fiscal year. In 2007, it took a record six referendums as town officials kept going back to the drawing board.

The Monroe Town Charter historically allowed voters to garner signatures to petition for a townwide budget referendum, rather than having it be decided at a Town Meeting. But in 1989, a Charter Revision Commission made the referendum vote automatic, sparking the annual battles.

A proposal to take away the automatic referendum in favor of elected officials deciding on the final budget was crushed in 2008, when residents overwhelmingly defeated the charter revisions by a vote of 4,591 to 1,041, an 81.5 percent margin.

The proposal would have allowed residents to petition for a referendum vote, but it would have been much harder.

Michael Manjos, chairman of the Board of Finance, said those pushing to “get rid of” the automatic referendum vote wanted to make petitioning for a referendum cumbersome, so Monroe would not have one every year.

“It’s definitely not the most common thing, having an automatic referendum,” he said. “It’s one of the things I love about the town. It’s not an incredibly efficient method, but most good government is supposed to be inefficient. There’s supposed to be checks and balances.”

Karen Burnaska, a former first selectman, remembers when large crowds used to pack into the Masuk High School gymnasium for annual Town Meetings. Because people petitioned for referendums every year, officials had made a townwide vote automatic.

“It was being petitioned to the polls for many years prior and there was a large contingent of people who thought the budget should be voted on by all the people and that there should be an automatic referendum,” she said.

The Monroe Taxpayers and Voters Association, a group formed by the late Frank Toth and Edward Stedman, expressed concern over rising taxes and demanded more accountability in how money was spent.

The MTVA rallied people to vote no on budgets and wanted to keep the ability to vote every year.

Burnaska also remembers a pro-education movement urging parents to vote yes to ensure proper funding for Monroe’s public schools. Because the education budget makes up such a large percentage of the town budget, it faces the most scrutiny among voters.

Voters have their say

Burnaska said the feeling among those in favor of ending the practice of automatically holding referendums was that if people did not agree with the budgets officials adopted, they could vote them all out.

The multiple referendums were costly and there were times when the town risked entering a new fiscal year without a budget.

Some residents used to accuse public officials of padding budget proposals, then making small spending cuts following each budget defeat to ultimately get the increase they wanted.

They also accused them of having funding for some items approved at sparsely attended town meetings after a budget passed, as an end run around the process.

“I always heard you pad the budget knowing it will go down the first time, so you have something to cut,” Burnaska said. “I don’t believe that. Overall, I think the budgets are put together with what elected officials feel is in the best interests of the community and meets its needs.”

“My thought always was, if we put out a reasonable budget to start with, it can pass on the first try,” Manjos said.

“The budget referendum is a critically important check on municipal and education spending,” said Town Council Chairman Jonathan Formichella. “It provides necessary insight to elected officials on the people of Monroe’s budgetary thoughts and objectives.”

Monroe’s budget process

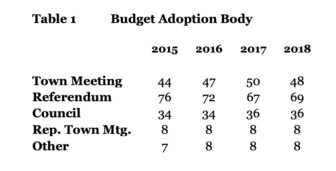

Of Connecticut’s 169 municipalities, 69 adopted their budget via a referendum vote in 2018 compared to 48 at a Town Meeting (in which residents who attend vote), 36 by a Town Council, eight by members of a Representative Town Meeting, and eight by some “other” method, according to an Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations (ACIR) study.

Of Connecticut’s 169 municipalities, 69 adopted their budget via a referendum vote in 2018 compared to 48 at a Town Meeting (in which residents who attend vote), 36 by a Town Council, eight by members of a Representative Town Meeting, and eight by some “other” method, according to an Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations (ACIR) study.

This information was shared by the Connecticut Conference of Municipalities.

Monroe’s budget approval process begins when the superintendent of schools works with administrators on a spending plan for Monroe’s public schools and presents it to the Board of Education.

The school board deliberates on the education budget in a series of workshops before adopting a proposal that goes to the first selectman’s office.

The first selectman comes up with a municipal budget for town services by working with department heads and can make revisions to the Board of Education budget, before presenting an overall town budget proposal.

The Town Council reviews the municipal portion of the budget and can add money, make cuts or keep it the same.

Then the Board of Finance reviews the town budget. It can make changes to specific line items in the municipal budget, but can only approve an overall dollar amount for education. The superintendent and Board of Education must decide how its final budget is spent.

The Board of Finance approves a final town budget proposal and sets a mill rate, so voters know the effect on their taxes before they go to the polls.

This year’s budget referendum will be held on Tuesday, May 2. The next fiscal year begins on July 1.

Low voter turnout

While drawn out budget battles are woven into the fabric of Monroe’s history, the town has enjoyed a more peaceful process in recent years.

Former first selectman, Steve Vavrek enjoyed some years of voters passing a budget at the first referendum, and current first selectman, Ken Kellogg, whose first budget passed for fiscal year 2018-19, has yet to experience a defeat.

However, it should be noted, there was no referendum vote for fiscal year 2020-21, due to Gov. Ned Lamont’s executive order during the COVID-19 pandemic. That year, the Board of Finance adopted the budget.

“We want to provide excellent town services and education in a fiscally responsible way,” Kellogg said.

The first selectman said the goal is to put out budgets that are perceived to be reasonable to people, so they pass it the first time.

“I think it’s great that we have this process,” Kellogg said of the referendum. “It gives voters the final say in the budget process and I support that.”

Despite being guaranteed the right to vote on their budget, only 12.94 percent of Monroe’s registered voters participated in the last referendum in May of 2022, compared to 12.74 percent turnout the year before.

Burnaska said voting in local elections and on the budget is one of the most important things a citizen can do, because those you elect have a say in the kind of education your children get, and on things such as the hours of the senior center and library, and the condition of the roads you drive on.

“It’s important on state and national levels, but for the daily living of an individual who lives in Monroe, it’s important to vote on the candidates and the budget and to become informed and involved,” she said.

“It’s really dropped off,” Manjos said of voter turnout. “It saddens me a little bit that more people don’t come to our meetings, but I also think there’s more confidence in what we’re doing.”

Manjos attributes some of the lower voter turnout to Kellogg proposing town budgets will small annual increases.

“My biggest concern is more people need to participate in government,” said David Ferris, chairman of the Board of Education. “It’s a rare opportunity that we get the privilege to participate in so much of our town government. We get to control our tax increases, yet we have very low voter turnout.”

Ferris said there is a need for many families coming from different countries, towns and states to learn about Monroe’s budget process. “It’s my hope that people will educate themselves and come out and vote,” he said.

A smoother process

In the past the Town Council was at odds with the Board of Finance, which would undo a lot of its changes to the municipal budget, Manjos recalled.

“It’s not the most efficient process, but it’s very effective and forces us all to work together,” Manjos said. “I think the boards in general have worked better together. Town Council and the Board of Finance traditionally, for the last 10 years, have a joint meeting just so we can understand our thoughts. And they come to our meeting as well, so it’s a good relationship.”

Manjos said there is a clear separation in functions, the first selectman and Town Council manage the town and decide on positions, while the Board of Finance figures out how to pay for it, manage debt and maintain Monroe’s AAA bond rating, which is the highest possible.

“The municipal side of the budget relies on collaboration,” Formichella said. “Town Council must be willing to work with the first selectman and Board of Finance in a collaborative fashion. Working together is the key to good government and joint meetings with the first selectman and Board of Finance promote fiscal discipline and accountability.”

Building trust

The superintendent and Board of Education had a strained relationship with the Board of Finance for many years, during a period marked by distrust.

In fiscal year 2011-12, the Board of Education’s proposed budget increase of $341,000 was wiped out by a Board of Finance cut that left only one dollar of new spending for then superintendent Colleen Palmer’s administration to work with.

Before getting an increase, Manjos said his board wanted the Board of Education to spend every dollar it already had in its budget first.

“We gave them some zeroes,” Manjos said. “They saw we were serious and we started working together.”

Ronald Bunovsky Jr., the longtime finance director for the town, became director for both the town and the school district in an agreement for a combined position in 2021, establishing stronger trust between the two sides.

“Ron Bunovsky was a wonderful change,” Manjos said. “He’s known on the town side too.”

“Everyone in the department under Ron came together to make it transparent,” Ferris said of the budget process. “I feel a strength in cooperation, not a loss in autonomy.”

He noted how the Board of Finance now has a member on the negotiating committee for the teachers’ contract, so they have more of an understanding of the issues. “People may not like the increase, but we’re able to understand the why,” Ferris said.

“I am extremely appreciative of the open lines of communication between myself, the Board of Education, the first selectman, the Board of Finance and other town officials,” Superintendent of Schools Joseph Kobza said. “I credit a lot of that to our finance director, Ron Bunovsky. It’s hard to find anyone who works harder than him. His combined role with the town and the Board of Education promotes transparency and trust.”

“Putting the budget together is difficult, time-intensive work, but at the end of the day we all want what is best for Monroe,” Kobza added.

The superintendent also credits the Board of Finance for its commitment to maintaining a contingency account for special education funding – “something that can vary greatly from month to month depending on enrollment, needs, and services.”

Ferris said there has been a significant effort by the Board of Education to spend money more efficiently and eliminate waste.

He recalled how the board went through all 2,000 line items in its budget a few years ago, removing lines that were not spent the previous year. “We had a line item for Chalk Hill books that we closed,” he said of the middle school that has been closed since 2012.

Ferris said the school board, finance board, first selectman and superintendent all communicate regularly, so there are no surprises.

All respectful comments with the commenter’s first and last name are welcome.