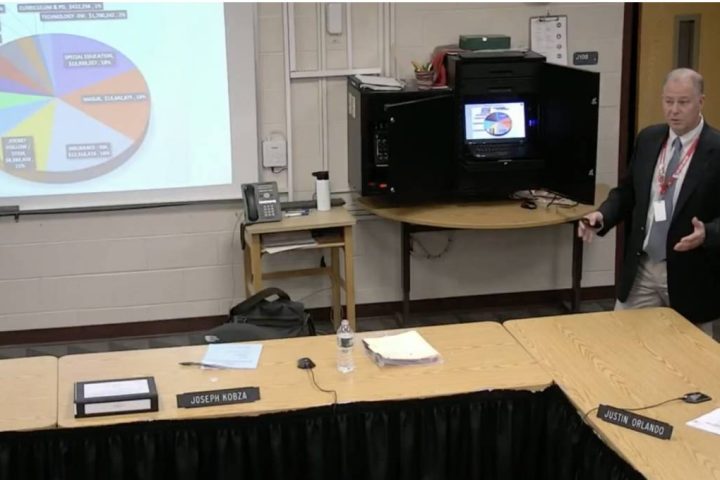

Frank Connelly, interim finance director for Monroe public schools, told the Board of Education the projected shortfall for special education was reduced from $307,000 to $91,000 at the board’s meeting Monday.

Superintendent of Schools Dr. Jack Zamary also told the board the district-wide spending freeze is still in place and educators expect to save around $411,000.

“We’re all working as hard as we can to find efficiencies and bring in the lowest budgets, while maximizing outcomes for students,” Zamary said in a telephone interview Thursday.

The spending freeze, which includes deferred maintenance for projects that do not have to be done right away, and holds off on discretionary spending in all of Monroe’s schools and Central Office, was put in place to save up to $300,000 for the year.

“We have a very good working relationship with the town,” Zamary said. “At budget time we were seeking an additional $300,000 in savings in this budget. This year’s freeze is how we’re making up for it. It’s not a device we want to use in the future.”

Zamary said his office is working with administrators throughout the district to make sure the $411,000 in savings can be realized.

Beyond their control

Last year’s special education budget had a deficit of $763,000 and the district’s self-funded health insurance plan had a shortfall of close to $1.5 million. The school district worked with town officials to close those gaps for the 2018-19 fiscal year.

“The challenge for us is always health insurance and special education,” Zamary said. “Our other budget lines are within budget. There’s a lot of variability with those costs, which seem to escalate and really wreak havoc on our budget.”

The superintendent said health insurance and special education costs are beyond the district’s control and it is legally bound to pay for it.

Since the Board of Education worked with the town on the 2018-19 deficits, the district switched to the State Partnership Plan 2.0, which has less volatility than being self-insured in years with a high number of claims. The superintendent’s office is also monitoring special education costs more closely.

“We set up a whole new practice for how we’re accounting for our special education costs,” Zamary said. “We want to have complete details for all costs in a shared resource, so that we have accurate, complete and transparent accounting.”

The resource is a master spreadsheet the district is using to project special education costs throughout the year and for the monthly reports it gives to the Board of Education, which will also be shared with the Board of Finance.

“It has numerous tabs, so we have an accounting for every student’s individual program, which feeds into a master sheet, because we would not share individual students’ information,” Zamary explained. “It’s all in one place. It’s all shared and we’re looking at the same thing.”

Prior to that, the superintendent said there was a “silo approach,” which was not working.

Securing state aid

Of special education, Zamary said, “it’s the most regulated part of our budget and one of the places we have the least control.”

However, school boards can apply for financial reimbursement from the state in the form of Excess Cost grants. When a school district spends 4.5 times its per pupil expenditure for high cost services for a special education student, Zamary said the state typically provides reimbursement for 70 percent of the amount beyond that.

But because it is based on individual students, a district could have some students receiving high cost services that are just below the minimum amount the district would have to spend to receive any financial relief at all.

Monroe public schools must submit its report to the state for an Excess Cost grant by Dec. 1, so Zamary said the district should have an idea of how much financial reimbursement it can expect by mid-November.

Zamary said the master spread sheet is being used to track it.

Settlements reduce costs

Every special education student has an individualized education plan (IEP), but families do not always agree it is the best one for their child. In those cases, a family can choose to file a lawsuit or to negotiate a settlement agreement with the district.

This year, Zamary said parents of six students decided to settle on a mutual agreement for their child’s IEP, which saved taxpayers the expense of lawsuits.