Erica Feher, 16, a Masuk High School junior, spent hours of her weekends sewing, so she could honor her great, great uncle, Edward Paul Hornyak, with a Quilt of Valor for his bravery in serving his country during World War II.

Hornyak, 93, of Newtown, was a ball turret gunner, shooting at enemy planes while aboard a B-17 Bomber in the U.S. Army Air Corps., which is now the Air Force. He squeezed into a fetal position in the small space, where his only protection was a glass bubble that jutted out from the bottom of the aircraft.

Hornyak’s family surprised him during a ceremony at the outdoor pavilion of the Veterans of Foreign Wars Hall in Newtown on Sunday, Oct. 13.

“We’re very proud of her and her capabilities,” Susan Feher said of her daughter, Erica. “She’s so talented just to put this quilt together. I am in awe. My uncle said it was the best day of his life.”

Hornyak is the great uncle of Susan’s husband, Paul.

Susan said Erica took up sewing eight years ago and her teacher asked if she wanted to make a Quilt of Valor in 2017. The Quilts of Valor Foundation, a national nonprofit organization, honors veterans with quilts made of patriotic materials.

Erica’s friend, Kathleen, wanted to make one for her grandfather, who is a Vietnam veteran, and Erica helped her make it.

“Erica wanted to do one for her family,” Susan explained. “She finished piecing the quilt sometime in the middle of August. It was sent out to get quilted by Mary Eddy and we got it back in September. She also made a pillowcase for the quilt to be carried in.”

During the ceremony for her great, great uncle, Erica said it took her over a year to make the quilt.

History of the Quilt

The Quilts of Valor Foundation began in 2003, when founder Catherine Roberts’ son Nat was deployed in Iraq, according to the history section of the nonprofit’s website.

In a dream, Roberts saw a young man sitting on the side of his bed in the middle of the night, hunched over. “The permeating feeling was one of utter despair. I could see his war demons clustered around, dragging him down into an emotional gutter,” she said.

“Then, as if viewing a movie, I saw him in the next scene wrapped in a quilt,” Roberts said. “His whole demeanor changed from one of despair to one of hope and wellbeing. The quilt had made this dramatic change.”

Roberts said the message of her dream was that quilts equal healing. She decided to form a volunteer team to donate their time and materials to make a quilt. One person would piece the top of it and the other would quilt it. The name of this special quilt would be the Quilt of Valor.

The first person to receive a Quilt of Valor was a young soldier from Minnesota, who had lost his leg in Iraq and was being treated at the Walter Reed Army Medical Center.

Chaplain John Kallerson opened the door for us at Walter Reed primarily because his wife Connie Kallerson happened to be a quilter,” Roberts said. “She impressed upon him how comforting quilts can be. John also saw the value of awarding quilts to his wounded, because of the message they carried that someone cares.”

“Quilts of Valor would be ‘awarded,’ not just passed out like magazines or videos,” Roberts said. “A Quilt of Valor would say unequivocally, ‘Thank you for your service, sacrifice, and valor’ in serving our nation in combat.”

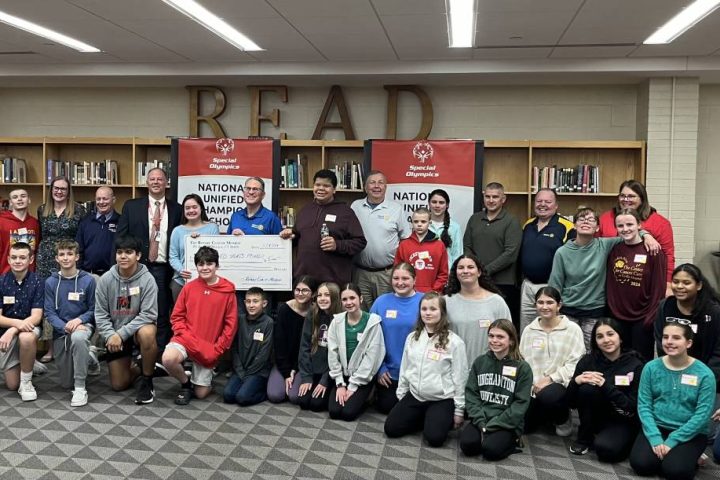

Since the organization started, 230,000 quilts were awarded by volunteers in all 50 states.

Uncle Eddie’s story

On Oct. 13, Edward Paul Hornyak and his wife were greeted with cheers at the VFW in Newtown. “He doesn’t know what’s going on,” one person called out. Then Erica walked in and stood next to her great, great uncle.

“I wish I knew what it was about,” Hornyak said with a laugh.

Jane Dougherty, co-coordinator for the Connecticut Chapter of Quilts of Valor, introduced herself and told Hornyak about the history of the foundation.

“Most of these quilts come through various hands and we all know that they’re going to a warrior, so they are infused with love, care and prayer,” Dougherty said, before adding of Hornyak’s quilt, “this quilt is extremely special because of who the quilt maker is.”

“This is my great uncle,” Paul Feher said. “He was my grandfather’s brother. He was a ball turret gunner in World War II. It’s probably one of the most dangerous jobs ever and every single person that did that made no bones about it, that they volunteered and this is what they wanted to do.”

Feher said his Uncle Eddie always told him stories about the war. “I’ve been thinking about this a long time and Erica’s been wanting to do this,” he said, “and she spent I don’t know how many weekends laying this out — and we’re just super proud.”

Feher said Hornyak helped a lot of Hungarian people, who were taken prisoner. “He saved a lot of their lives, because he knew enough how to communicate with these people,” he said.

Feher said Hornyak was in the occupation after the war was ending and helped a lot of Hungarian people who were taken prisoner, bringing those who were starving into the military mess hall to eat.

Hornyak, whose parents were from Hungary, grew up in “Hunk Town,” a Hungarian neighborhood on the west side of Bridgeport. “When I went into the service I spoke Hungarian very well,” he said. “In fact, the people I met in Hungary, who were Hungarians, thought I was born there. That’s how well I spoke it then.”

Hornyak enlisted and volunteered to go to Germany, because the U.S. Army Air Corps needed ball turret gunners. “And the only reason I was made a ball turret gunner was because of my size,” he said as his nephew helped him up from his chair, revealing his short stature.

Laughter filled the pavilion. “It runs in the family,” someone called out.

“Everybody on the plane was like 6’8, 5’8, 5’10, 6’4,” Hornyak said. “The tail gunner and I were the short ones. He had to be on his knees all the time as a tailgunner. You weren’t allowed in the turret on take off or landing. By the way, that door to crawl in there was only about like this,” he added, holding his hands a short distance apart. “I weighed 127 pounds.”

“When I enlisted and they took me, I’ll never forget the day I got the letter to report to duty,” Hornyak said. “My Dad looked at my mother and said, ‘I think we better cash in our war bonds, because if they take him, the war is lost.’ And that’s the truth. I hope he said it as a joke,” Hornyak said, getting more laughs.

Hornyak said he was in the cadet program, where he was trained to either be a pilot, a navigator or a bombardier. “There were 1,300 or 1,400 of us,” he recalled. “I was a pilot. The tailgunner on the plane I was assigned to went through the school with me.”

“By the way, I had 19 missions over Germany,” Hornyak said, before getting emotional looking down at a handkerchief. “You’ll have to excuse me. When I think of my buddies, you see …”

Eddie lands the plane

Among the stories Hornyak shared was a time when the B17 he was on was “pretty well shot up.” The pilot and co-pilots’ legs were bleeding, so neither could fly the plane.

“We had a medic thank God,” Hornyak recalled. “Both were laid out right behind the cockpit of the plane. Behind the cockpit is the radio operator. The medic was bandaging them up and taking their belts to stop the bleeding. Johnny called me up and said you better takeover. The tail gunner became my co-pilot.”

The plane was on its way back to France, where Hornyak was stationed.

“As we got close to our base to land, a general said, ‘do you still remember how to land the plane?’ I said, ‘I think so.’ The captain said, ‘do you think you can land the plane without me?’ ‘I think so.'”

Hornyak said it had been six months since he was allowed to land a plane, but he managed to land the aircraft safely that day.

The military veteran will always hold fond memories of those he served with and the quilt Erica made for him is also close to his heart.

“I just went to his house and the quilt is on his bed,” Susan Feher said. “He is very proud of that quilt.”