MONROE, CT — Instagram, engaging TikTok videos and texts among friends can keep teenagers glued to their phone screens for hours, typing and scrolling to the next source of entertainment. But research also shows negative effects of social media, including cyberbullying, increases in depression, more exposure to tropes such as racism, hate and misogyny, decreases in sleep and in-person social interactions.

Masuk High School teachers join other educators across the nation in their growing concern over cellphones causing distractions in their classrooms, taking away from instructional time and impacting upon social emotional learning. There has also been a rise in bathroom breaks as an excuse to leave class to text with a friend.

Masuk had a policy requiring students with cellphones to keep it secure and out of sight, but Principal Steve Swensen said it was not effective enough.

“If kids could control it in their pocket or their backpack, I probably wouldn’t be here,” Swensen told the Board of Education at its June 3 meeting. “But they can’t. They genuinely cannot control that — and what it does boil down to, is an impactful loss of instructional time, at a time when instructional time is so, so important for so many kids.”

Swensen and his school’s Academic Climate Committee came up with a plan to combat the problem, which will go into effect this coming fall with the full support of Superintendent Joseph Kobza and the Board of Education.

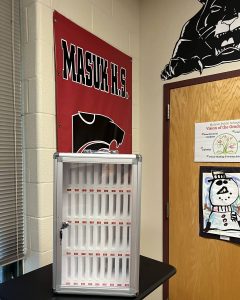

Every teacher will have a portable phone locker with a handle on top and 36 numbered slots, to collect cellphones from students at the beginning of each class. Each student would be assigned a numbered slot.

“If a teacher catches a student with a phone, it’s taken to the office. It’s an administrative issue,” Swensen said of students who do not hand over their phone.

Students will have access to their phones during study halls, lunchtime and passing time, according to the new policy.

Swensen sent out a letter informing parents of the new policy, along with links to information showing the negative impact of smartphones in the classroom.

“There is a mountain of research supporting this policy,” Kobza said. “We know that designers of social media apps have one major goal — to keep the customer engaged online for as long as possible. Algorithms are created to get users addicted.”

“It is impossible to attend to both your phone and classroom instruction at the same time,” he said. “In addition, so many of the social-emotional issues that kids struggle with today originate from their cellphones. This policy is a great first step to address the impact to instruction, as well as the social emotional benefits of phone free time in school.”

Though locking up phones, then returning the devices to students after class can take about three minutes, Swensen said the remaining 72 minutes of a 75 minute period will be more interactive with less instructional time lost.

More than three quarters of the nation’s schools (76.9 percent) prohibited the non-academic use of cellphones or smartphones during school hours in 2019-20, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

In news articles on the issue, principals said they have seen less fights connected to social media posts and more students talking to each other in the hallways, rather than walking with their heads down, while looking at their phones.

Aside from removing the distractions, many report a reduction of the phones as a source of stress and anxiety among students.

Changing norms

Swensen shared excerpts of a video from Jonathan Haidt, a social psychologist and best selling author, called “Smartphones vs. Smart Kids“, illustrating the national problem and offering potential solutions.

Haidt recommends taking collective actions to change societal norms.

“If you just say, as my kids schools did, ‘oh, we have a phone ban, you’re not allowed to use your phone during class. You have to put it in your pocket,’ it would be like a heroin recovery clinic saying, ‘you can take your heroin into our facility, but you must not shoot up in the bathroom.'” — Jonathan Haidt

“I tell my daughter, ‘you can’t have a phone in seventh grade,’ and she says, ‘everyone else does. I’m isolated. I won’t know what’s going on,'” Haidt said of how difficult it is for parents to take action on their own.

“But what if half the kids, half the families, did it?” he said. “Well, then it would be easy because all she could say is, ‘but Daddy, some of the kids have phones.’ That’s not a very good argument.”

Haidt calls for the collective action of allowing no smartphones before high school (until age 14) and no social media before age 16.

“So if you just establish these as norms, minimum standards before high school, it doesn’t make sense to give a distraction device, an experience blocker basically, to a child, especially when they’re just beginning puberty,” Haidt said.

If parents want their children to be able to communicate, he suggests giving them a flip phone.

“Flip phones are great. They’re made for communication,” Haidt said. “The Millennials went through life with them and that’s why they’re okay. Gen Z went through puberty on iPhones/Instagram, and that’s why they’re not okay.”

Haidt said U.S. law considers age 13 to be internet adulthood, giving teens the right to sign contracts with tech companies and to agree to give away their data. “It had nothing to do with mental health,” he said of the reasoning behind it.

He suggests changing the age to 16 and his third recommendation is phone free schools.

‘Distraction devices’

Haidt recalled an article he wrote for The Atlantic entitled, “Get Phones Out of Schools Now: They impede learning, stunt relationships, and lessen belonging. They should be banned,” where he reviewed the evidence of what happens when kids have phones in schools.

“If you just say, as my kids schools did, ‘oh, we have a phone ban, you’re not allowed to use your phone during class. You have to put it in your pocket,’ it would be like a heroin recovery clinic saying, ‘you can take your heroin into our facility, but you must not shoot up in the bathroom,'” Haidt said. “There are all kinds of harms from kids having phones in their pocket.”

He said educators had believed National Assessment of Educational Progress scores — for reading and math — dropped off because of COVID 19, but noted how the drop actually began after 2012, which he attributes to smartphones.

“Once kids have a distraction device in their pocket, they’re not capable of paying full attention to a teacher,” Haidt said. “They’re not paying full attention to the kids sitting next to them in the lunch room. Because they have their phone in front of them, they’re all multitasking. No one is present.”

Aside from academic progress tanking when kids have phones in their pockets, Haidt said, “it’s also social belonging and inclusion.”

He shared some results from a Pisa Survey from 2002-2018, which showed “no real change” in students feelings of loneliness and belonging in school, and said that changed significantly by 2015, when most kids had smartphones and said they do feel lonely at school.

Haidt said Yondr pouches or a phone locker are the only ways to stop kids from checking their phones during class.

Responsible use

Swensen told the Board of Education that he and the Academic Climate Committee went back and forth on favoring a total cellphone ban from 7:25 a.m. to 2 p.m., verses what he believes is the more controllable solution of protecting instructional spaces.

Swensen said lockable Yondr pouches would be best for a total ban, but would cost the school about $60,000. He also noted there is a YouTube video showing how to beat a Yondr pouch, so it could be futile.

Asked what some other schools are doing, Swensen said Fairfield and Bethel schools use numbered pockets for phones, similar to what was used for calculators. In the event of an emergency evacuation, he said it will be easier for Masuk teachers to grab their portable phone lockers by the handle and carry it outside.

Dennis Condon, a board member, asked if students could check their phones out for bathroom breaks and Swensen said no, because there is no need to take it to the bathroom.

Swensen expressed his hope that locking the phones at the beginning of class will reduce the problem of students saying they have to go to the bathroom, only to go to their locker in the hall to use their phone.

“I don’t want to put a teacher in a position where they say to a student, ‘no you can’t go to the bathroom,'” he said.

Condon asked if there is a way to make cellphones not work inside the bathrooms, but was told that solution could be more costly.

Is there a case for phones?

In a preliminary survey among teachers, cellphones ranked number one among the top five distractions. Swensen said teachers receive constant reminders about distractions.

“If you have kids with phones, their attention is here. It’s there. It’s there,” Swensen said. “I remember a teacher telling me I had the attention span of a gnat. Well, I think a gnat nowadays would probably be somebody focused.”

Swensen said getting kids off screens will lead to sustained periods of interpersonal interactions with their peers in a classroom setting.

“I think we owe it to our kids to teach them responsible use,” Swensen said, “even if we have to do the hardest thing and take it out of their hands to do it.”

While the argument could be made that a phone is basically a computer in kids’ hands, Swensen said laptops and Chromebooks are much better suited for work than phones are.

Swensen said teachers were asked if they ever allow kids to use cellphones for work they could not do with another device. “The bottom line is no,” he said.

“Some of the parents’ concerns were, ‘what if there is an emergency?'” Swensen said. “In reality, in an emergency setting the last thing you want is for everybody to hop on their cellphone.”

Swensen said parents who need to be in touch with their son or daughter during the school day can call the main office as families have in the past.

“Nobody has argued against the rationale that we need to protect instructional time,” Swensen said. “Nobody argues with me that it’s not an important thing to do.”

An imperfect solution

Justin Orlando, a board member, said students’ social interactions are important to him, so he favors locking students phones up at the beginning of the school day and giving it back to them when they’re going home, rather than playing the game of locking up phones for each class, then unlocking them all day long.

“Now, they’d have their phone between classes,” Orlando said. “They’re not talking to their friends. They’re looking at their phones.”

Swensen said there is not a centralized area to lock the phones up for the day. Instead, lockers are spread out through the entire building.

“If I thought there was a feasible way to manage it, I would do that,” Swensen said. “I do think full day is the way to go.”

“I think it’s a good plan,” Condon said of the portable lockers. “I don’t think there’s any perfect plan. We’re all addicted to our phones.”

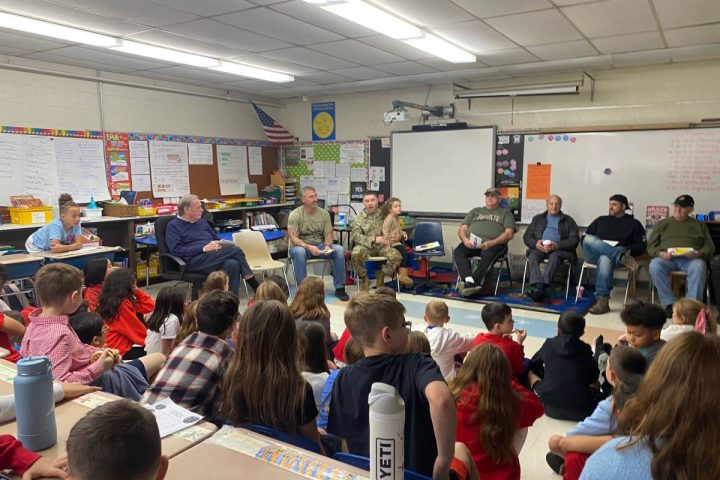

Jockey Hollow

Board of Education Chairman David Ferris spoke of having consistency among the district’s five schools, especially between Jockey Hollow Middle School and Masuk.

“We have a different imperfect policy at Jockey Hollow,” Principal Julia Strong said. “It’s no phones all day, so the cafeteria is loud and there’s social interaction all the time.”

Strong said phones have to be in students’ lockers. If a rectangular outline can be seen in someone’s sweatpants pocket, she said the phone is taken away, regardless of whether it rings or not.

Jockey Hollow students do not change classrooms as much during the day as Masuk’s do, so the lockers can usually be seen by teachers through their classroom windows, according to Strong.

“We do have the battle of, ‘I have to go to the bathroom,’ every 40 minutes, all day long, so we absolutely have those conversations,” she said, “and it’s not an easy conversation, because you always pick somebody who does have to go to the bathroom every 40 minutes. Then it’s a terrible conversation, so we haven’t solved it completely either.”

All respectful comments with the commenter’s first and last name are welcome.