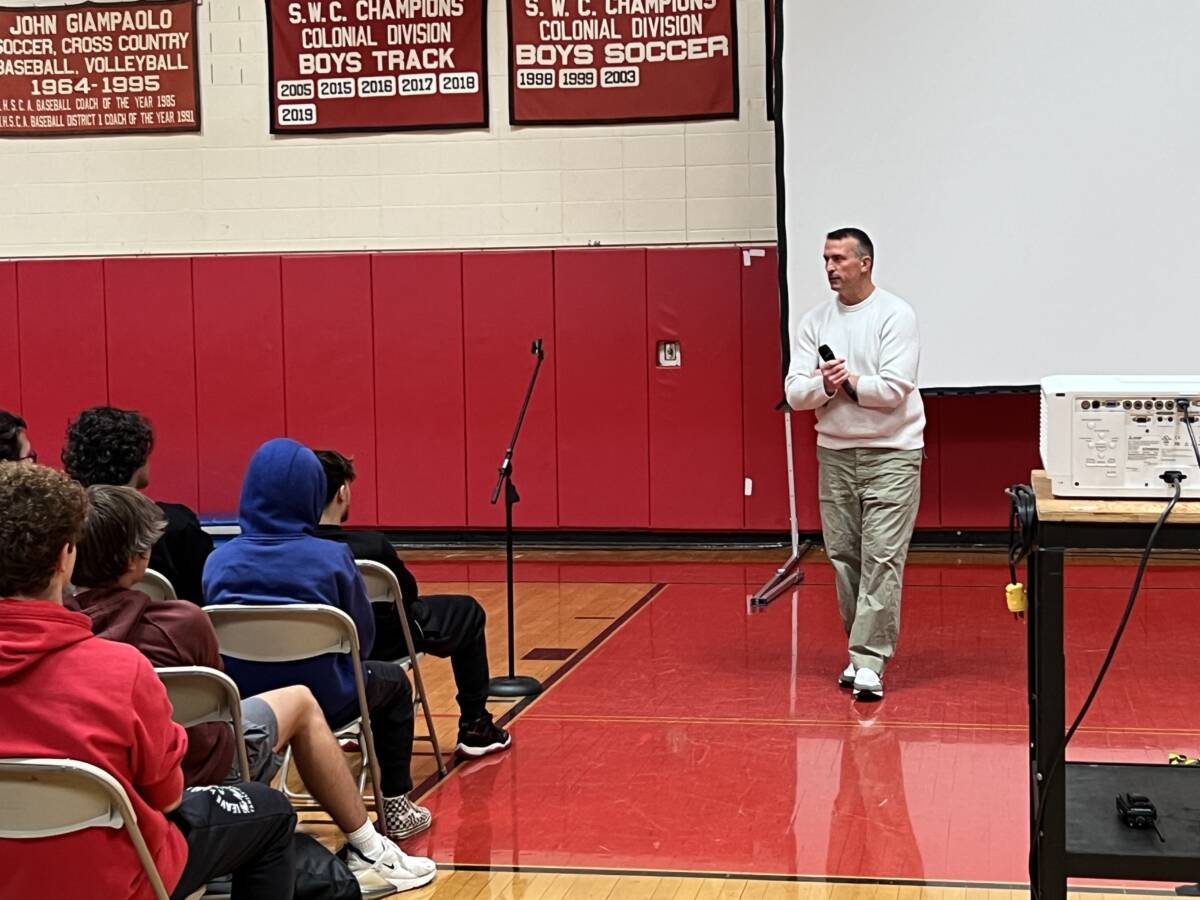

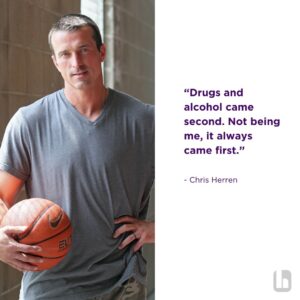

Chris Herren, a basketball star who nearly lost everything to drugs and has since become a well-known advocate for sobriety and recovery, shared his cautionary tale with Masuk High School parents and students in separate presentations earlier this week.

Growing up in a household with an alcoholic father, Herren traces his problems to his teen years, hanging out in the basement with friends, drinking beer from Solo cups and smoking blunts in the backseats of cars.

Of the 15 players on Herren’s high school basketball team, seven became heroin addicts later in life.

“We think about the worst day and not the first day,” Herren said.

He said his goal was to reach the Masuk students who may be struggling in silence, before things spiral out of control for them.

He started the Herren Project: Addiction Recovery Nonprofit Organization and Herren Wellness, which offers an approach to recovery combining holistic wellness with medical and clinical collaboration for the continuity of care.

He’s made appearances before over a million high schools and organizations, including presentations to famous athletes like Tom Brady, Peyton and Eli Manning and Lebron James. He had previously spoke at Masuk in 2016.

Herren’s latest visit to Masuk was made possible through opioid lawsuit settlement funds the town of Monroe received. First Selectman Ken Kellogg established an administrative team to provide recommendations to use the money in a way consistent with the settlement agreements.

The town’s first expenditure of these funds was used to provide a school-based program to prevent drug misuse that was highly recommended by Superintendent Joseph Kobza. Herren’s presentations were authorized by the Town Council.

Monroe Health Director Amy Lehaney set up a booth in the Masuk lobby during Herren’s first presentation to parents inside the auditorium Monday night. She brought information on cannabis, opioids and vaping, including what vape cartridges look like.

She also held a raffle for a lockbox for medication, prescription drugs and edibles.

“I think it’s great,” Lehaney said of how the settlement funds are being used. “I think focusing on youth is the best way to avoid future opioid addictions.”

Herren’s rise and fall

Chris Herren shared his story with parents of Masuk High School students in the auditorium on Monday night and spoke to the entire school in the gym the next morning.

From all outward appearances, Herren’s life seemed like a dream. He was a star basketball player at Durfee High School in Fall River, Mass., and a McDonald’s All-American sought after by the nations biggest schools, including Boston College.

The hometown hero went on to be drafted by the Denver Nuggets then traded to his favorite NBA team, the Boston Celtics, while competing with superstars like Michael Jordan and Shaquille O’Neal.

But it was a dark period in his life. An opioid addiction made him depend on drugs just to get himself onto the basketball court and a string of positive tests and arrests led to embarrassment for him and his family along the way.

He was kicked out of Boston College and had to finish his college basketball career at Fresno State. After being drafted by the Denver Nuggets with the 33rd pick in 1999 and traded to the Celtics injuries and drug use soon ended his NBA career.

After squandering opportunities to play basketball overseas, he sold his two children’s PlayStations, a vacuum cleaner, everything he could get his hands on to get money for his addiction.

Herren had four overdoses, once losing his heartbeat for 30 seconds before being revived.

“This is the hardest thing you’re going to do. Call your wife and tell her you’ll disappear. But before you hang up, ask her to tell your children their father died in a car accident. It’s time for you to be dead to your family. You’re a no good, scumbag junkie.” — A Drug Counselor to Herren

After leaving rehab to be with his wife for the birth of their third child, he left the hospital to get cigarettes, but instead went to a liquor store.

“You broke my heart a thousand times, but look at what you’re doing to our children,” Herren’s wife Heather told him. “I love you. I’ve known you since seventh grade, but you have to say goodbye to your kids. You’re never going to see them again.”

Herren hugged his children and wanted to commit suicide, until a friend of his late mother tapped him on the shoulder in the hospital and told him his mother wanted her to give him the support she could no longer give.

Herren was high when he showed up at rehab and a counselor gave him a tough message that changed his life.

“This is the hardest thing you’re going to do,” he told Herren. “Call your wife and tell her you’ll disappear. But before you hang up, ask her to tell your children their father died in a car accident. It’s time for you to be dead to your family. You’re a no good, scumbag junkie.”

“I walked out of the office and thought it was the worst day of my life,” Herren recalled. “I thought about my kids’ reaction to the news and my mother. I fell to my knees.”

Herren has been sober since August 1, 2008. “I thank God for that man’s words,” he said.

He said the first 13 years of sobriety was a breeze, but the last two years have been a constant struggle to avoid a relapse.

Back to 1994

Herren remembers when a recovering addict spoke at Durfee High School when he was a star basketball player growing up. He thought, “I won’t turn out like this loser.”

“In 1994, I had an opportunity to sit in a gymnasium and pay attention,” he told Masuk students inside their gym, “and right now I would give anything to go back to 1994 and listen.”

Herren remembers the first time he tried cocaine. Two female students were doing lines in his dorm room at Boston College and he decided to leave, before one encouraged him to join them.

“It won’t kill you,” she said. “Just put it on your gums. It will just numb it.”

After Herren did that. She put a line of cocaine on a desk and he took a rolled up dollar bill from her.

“I told myself, ‘one line and I’ll never do it again,'” Herren recalled. “I didn’t know it would take 14 years.”

When Herren drank and smoked blunts with his friends as a teenager, he said they laughed at the kids who chose not to.

“I would see kids not do it and say to myself, ‘maybe he has something I’m missing man,'” Herren said. “Kids that can hang out in friends’ basements and can be themselves, these kids are warriors to me.”

He said the pull of his addictions are strongest when he doesn’t feel comfortable being himself.

Herren’s father was an alcoholic and when his mother decided to divorce him, Herren was 10-years-old. He remembers hugging his mother and asking her to take him with her.

“I want you to know something,” he told her, “because of everything I’ve seen, you won’t have to worry about me.”

But years later, his mother found him in the woods behind his school, drunk on Miller Lights.

“I wish someone pulled me aside and told me what Miller Lights were doing to my family,” Herren said. “This isn’t about drugs. It’s about family.”

If he could see his late mother again, Herren said he would hug her, tell her he loves her, show her pictures of her grandchildren, then ask one question.

“Honest to God, before I let go of her, I’d ask, ‘how come you didn’t ask me why? As much as you loved me, weren’t you curious?'”

Herren’s two oldest children do not drink or use drugs. If he found out his youngest had, Herren said he would not ask where he got it, how much he did or who may be a bad influence.

Rather, Herren said he would ask what was wrong that made his son decide he needed to get drunk or to use drugs.

Herren encouraged any students who are going through tough times to reach out to someone they trust.

After the presentation, Assistant Principal Ian Lowell reminded students that the Masuk school community cares about them and there are counselors, psychologists, teachers and administrators to turn to.

“It’s an honor to do this,” Herren said. “I understand this isn’t for everyone,” adding of his own experience with a high school speaker in 1994, “I needed it and I wish I listened. God bless you.”

All respectful comments with the commenter’s first and last name are welcome.